However, the inner workings of an electric vehicle (EV) are very different to a conventional car – as is the ‘refuelling’ process.

This guide offers an overview of how electric cars work and how to get the best from them.

How an electric car works

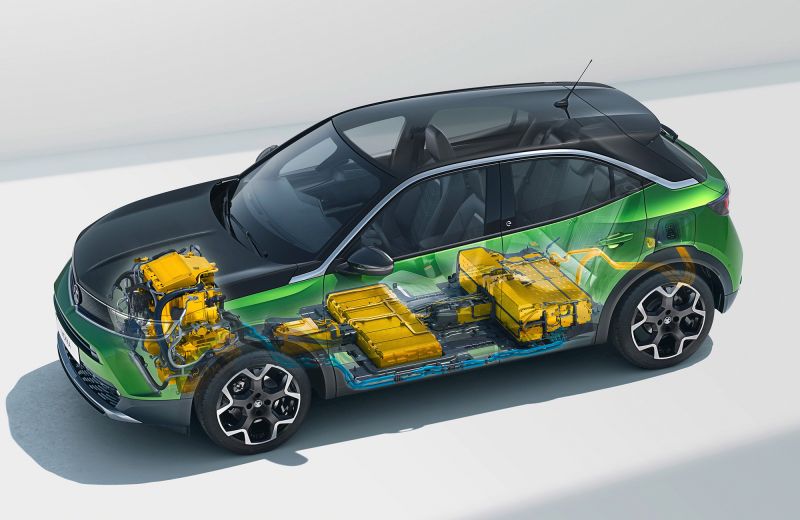

An internal combustion engined (ICE) car is powered by liquid fuel mixing with air – the combustion process – which creates energy to turn the wheels. An EV is charged via a cable and powered by energy stored in rechargeable batteries.

These batteries power an electric motor – or, in some cases more than one motor – which provides the drive.

A process called regenerative braking happens when you lift off the accelerator, converting kinetic energy – from movement – into electricity. This is then fed back into the battery.

Harnessing electric power to move a vehicle is nothing new. The first electric cars appeared in the 1840s, but didn’t become mainstream because rechargeable battery technology didn’t exist. Forty years later, it was a different story, and the very first electric cars as we know them today took to the roads.

- Electric car leasing explained – EV financing vs buying

- Types of electric vehicles – EVS explained

However, the limited driving range of early EVs, combined with the arrival of electric starters and mass production for ICE cars, made them less practical. It wasn’t until the 1950s that EVs began to fight back. Developments from the 1960s to the 1990s saw electric cars make a determined resurgence, and in the early 2000s electricity began to challenge petrol and diesel as the potential fuel of the future.

Lithium-ion battery technology was one breakthrough that helped EVs gain traction, but their range was still low. Most early EVs could only cover up to 100 miles on a single charge.

Stricter environmental legislation has forced car makers to speed up EV development. The past five years have witnessed many cars break the 200-mile barrier, with more premium EVs able to drive beyond 300 miles.

Ever-evolving batteries and fast-charging technology have also been key to the take-up of EVs, and with solid-state batteries on the way, shorter charge-times and longer ranges will make them even more accessible.

An EV has many fewer moving parts than an ICE car. The electric motor acts like an engine of an ICE vehicle, its power sent to the wheels via a single-speed transmission. An inverter converts direct current (DC) electricity stored in the battery to alternating current (AC), so the motor can use it.

EVs also have a charging socket for putting electricity back into the battery. Find out about the different connectors, charging speeds and charger types in our guide here.

RAC Breakdown Cover

Join the RAC and get breakdown cover. Our patrols fix 4 out of 5 vehicles on the spot, with repairs done in just 30 minutes on average.

What is the difference between electric cars and hybrids?

Not all ‘electrified’ cars are electric. In fact, there are four basic types of electrified vehicles.

Electric vehicle (EV)

A pure EV or battery-electric vehicle (BEV) has at least one electric motor powered by batteries that are recharged. Most modern EVs can cover between 130 miles and 400 miles on a single charge, depending on the car and battery size. This distance is called the range.

Plug-in hybrid (PHEV)

A plug-in hybrid vehicle (PHEV) uses batteries to power an electric motor, but also has a petrol or diesel engine as a ‘back-up’ power source. Batteries are charged in the same way as an EV, but the all-electric range is much smaller.

Hybrid (HEV)

A hybrid is similar to a PHEV in that it uses both electric and ICE power sources. The key difference is that its batteries cannot be externally recharged. The engine is the main source of power, while the batteries are used at low speeds to save fuel.

Fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV)

An FCEV uses hydrogen as a power source. When hydrogen is mixed with oxygen, electricity is created to power the car. The refuelling time and range are similar to an ICE vehicle, but the infrastructure is limited.

Advantages of an EV

- Zero emissions make a BEV the ‘cleanest’ vehicle you can drive

- EVs offer lower running costs and tax benefits

- They are relaxing to drive, quiet and feel quick compared to most ICE cars

Disadvantages of an EV

- Fully charging an EV’s batteries takes the longest time of all the electrified vehicles – and much longer than refuelling an ICE car

- The total driving range of an electric vehicle (how far you can drive on a full battery) is shorter than most ICE cars, although the gap is narrowing

- EVs are often more expensive to buy or lease

Charging an electric car

Provided you know which connector you need, charging an electric car is easy. Drive up to a charger, connect the cable and plug to the car’s socket, then initiate the charge via a smartphone app or on the charger itself.

The charging process takes varying amounts of time depending on the charge point your EV is connected to. A basic rule is that the higher the power rating, the faster the charge.

Another important thing to know is the difference between kW and kWh. A kilowatt (kW) is a unit of electric power, usually used to define the output of EV electric motors and to denote charging speed (e.g. 50kW). A kilowatt-hour (kWh) is a unit of energy measured by both power (kW) and time. The capacity of an EV battery is usually measured in kWh (e.g. 40kWh).

When you charge an EV at home, the slowest charge will be a connection to a domestic three-pin socket. Using a Kia EV6 with around 300 miles of range as a guide, a full charge on a 2.3kW home socket will take almost 33 hours. A 10-100 percent top-up on a 7kW wallbox takes just over seven hours.

More powerful fast chargers bring down charging times dramatically. A 50kW charger fills the EV6’s battery from 10-80 percent in 73 minutes, with a 350kW charge point slashing that to just 18 minutes. Most EVs can accept 100-150kW fast charging, so bet on around an hour for a 10-80 percent refill.

Living with an electric car

To get the best from an electric car, you need to plan ahead. This is because you may need to charge en route to your destination.

If you have a home charge point, it’s always easiest to refill the batteries there, although smartphone apps and websites – such as Zap-Map – allow you to locate possible charging stops. Pre-heating or pre-cooling your EV’s cabin before setting off also saves range later.

Read more on how far you can drive an EV here.

The typical range of EVs has increased massively during the past five years. Small cars such as the Peugeot e-208, Renault ZOE E-Tech and Vauxhall Corsa-e can officially manage at least 200 miles, while the flagship Tesla Model S can manage more than 400 miles. Unlike a decade ago, longer journeys can now be undertaken without ‘range anxiety’.

Energy providers offer EV-focused tariffs that can save you money when charging. Many are dual-rate – electricity is cheapest overnight when your EV is charging – or single-rate, where the same rate is paid throughout the day, but discounted if you are an EV owner.

Conclusion

The simpler make-up of an electric car means it is likely to be more reliable – and cheaper to run – than an ICE equivalent. Understanding how an EV works will help you maximise its advantages.

Due to its technical expertise with EV powertrains, the RAC is leading the way when it comes to supporting drivers in the switch to electric vehicles.

An increasing number of our patrol vans have built-in emergency mobile charging systems that can give an out-of-charge electric car enough power to be driven a short distance home or to a working charge point. Our All-Wheels-Up recovery system also allows our patrols to rescue electric cars safely without the need for a flatbed.

RAC Breakdown Cover

Join the RAC and get breakdown cover. Our patrols fix 4 out of 5 vehicles on the spot, with repairs done in just 30 minutes on average.